Ukraine, Russia and the Arabs

Merissa Khurma | Wilson Center

As the Russian-Ukraine crisis continues to dominate headlines globally, different corners of the world are watching closely, waiting to see whether Russia will invade or de-escalate. One of these corners, which has received less attention, is the Arab world. Akin to other regions, it will be impacted in more ways than one. First, the Arab region continues to be a theater for great power competition, particularly between Russia and the United States. Second, it is home to some of the world’s largest oil and gas producers, whose energy production future is affected by rising tensions and the outcome of the crisis. In addition, skyrocketing oil prices in recent days have impacted financial markets in the Arab states of the Gulf, where stocks moved in different directions in reaction to “geopolitical tensions in Eastern Europe.” For energy importing countries such as Jordan and Lebanon, higher fuel prices are intrinsically linked to political anxiety at home. Third, many Arab countries will likely suffer food shortages if war erupts, as both Russia and the Ukraine are among their top sources of cereal imports.

Perceptions and Great Power Competition

An emboldened Russia in Europe, or the perception of it, will further strengthen its hand in Syria, where it has supported President Bashar Assad and kept him in power for the last decade. This is happening against the backdrop of what many Arab analysts see as a U.S. retreat from the region. There are simply more reasons, and opportunities, to lean more strongly toward Russia in the eyes of many Arab governments. Egyptian author Tarek Osman noted that Russia has “been trying to fill some of the void,” left by decreased U.S. presence, “in the Eastern Mediterranean and the most volatile parts of North Africa,” as well as “in some of the circles related to the security of the Gulf,” including closer cooperation between Russia, Saudi Arabia, and with the United Arab Emirates. Osman added that Arab countries are “looking at the Ukraine situation to assess whether America is indeed going to show strength – and importantly, creativity – so as to deny Russia its objectives,” or else “will Russia get what it wants.”

As it stands, a quick glance at headlines and analyses in the Arab media show, in many cases, how the Arabs are ‘reading’ geopolitical tensions in Europe and the Biden administration’s handling of the crisis in Ukraine. Some headlines and opinion pieces frame the crisis in terms of “American escalation” toward Russia, in stark contrast to how American and Western media sees and reports on the crisis. One analyst cited how the Ukraine-Russia crisis provides an important lesson on the power and influence of what he calls the “American and western media machine,” and the “hysteria” it created around a Russian invasion that had prompted even the Ukrainian Foreign Minister to urge calm.

In the words of another Arab columnist in the Bahrain based daily newspaper Akhbar Al Khaleej (Gulf News) for example, America and its NATO allies are “engaged in an open conflict with Russia over Ukraine and is escalating the situation to the brink of war under the pretext of Russia threatening Ukraine’s independence.” An Amman-based analyst with deep knowledge of Russia in the region told me that most of the coverage of the Ukraine crisis in the Arab media is recycled from newswires or reports by major international newspapers. “Rarely do you see critical pieces of Russia’s military intentions in Ukraine,” she mentioned. Another factor that helps Russia’s image in the standoff with the West is that most Arabs view Russia through the prism of the old alliances the Soviets established across the region. “Many see this conflict as an internal one between Russia and Ukraine,” she noted.

This analysis on Arab perceptions holds water when we look at the most recent findings of the Arab Youth Survey, specifically in regard to how young Arabs see their respective countries’ allies and foes. 70 percent of youth in the 50 Arab cities surveyed see Russia as an ally and only 26 percent see it as an enemy. In contrast, 57 percent see the United States as an ally while 41 percent see it as an enemy. It is important to note here that Arab youth represent more than 60 percent of the region’s population.

Given these views, some analysts are also openly welcoming geopolitical movements away from a unipolar world in which the United States is the hegemon. They are hoping these developments mark a possible return to a bipolar world, or a shift towards a multipolar world in which Russia is joined by China in competition for power with the United States. Great power competition provides an opportunity for regional states to assert themselves and find more willing alliances.

Energy Links and Balancing Relations

Zooming closer into the Arab states of the Gulf, some of which are the largest energy producers in the world, puts the spotlight on how and why the Ukraine-Russia crisis deeply impacts the Arab region’s economic health. Akin to other non-GCC countries in the Arab world such as Egypt, the states of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) try to maintain “balanced relations with major world powers,” according to Abdullah Baaboud, an Omani policy analyst and academic. The Ukraine crisis, he noted, “puts them in an awkward position if they have to choose a side,” especially if the situation leads to war, with looming sanctions against Russia affecting “their growing economic and military cooperation with Moscow.” Some may already have chosen a side. Saudi Arabia has reportedly decided to stand by an agreement between OPEC and Russia (or OPEC+) rather than “pump more crude to tame the market” which would help the United States and its western allies. This is what the Kingdom has decided, for now at least.

Baaboud explained that the GCC states have a “good working relationship with Russia in oil and gas through OPEC+ and the Gas Exporting Countries Forum,” adding that US pressure on these states will “negatively affect their cooperation with Moscow and diverting their LNG to Europe could have impact on their long-term agreements with Asian countries.” These qualms felt in GCC states circle back to their perceptions of great power competition worldwide and their own region. They “see Russia as a power they want to have good relations with, especially [given] that there is a perception that the US is abandoning the region,” Baaboud said.

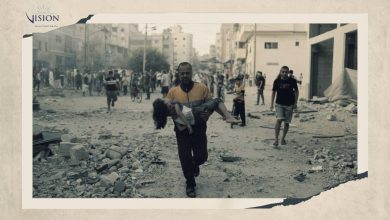

Beat the Wheat Crisis

Both Ukraine and Russia are among the world’s top wheat exporters (representing about 29 percent of global supply), on which many countries in the region depend. Egypt, Lebanon, Yemen and the Arab countries of North Africa (particularly Libya and Morocco) are facing an impending “bread” crisis as wheat prices continue to soar with rising tensions on the Ukraine-Russia border. Lebanon and Yemen are especially vulnerable as they grapple with their own food security challenges, the latter deeply in conflict that has killed around 377,000 Yemenis. Alarmingly, 60 percent of which died due to hunger or other health related issues.

Furthermore, Egypt, as the most populous Arab country with over 100 million people, is especially vulnerable to rising wheat prices, which it imports primarily from Russia and Ukraine. Even as Egyptian officials downplay the negative impact of the Ukraine-Russia crisis on wheat imports to Egypt, history is a brutal reminder of how soaring bread prices caused riots as recently as 2017 and as far back as 1977. Egyptians call bread “Eish” meaning “life” because so many lives depend on it. So, when it is inaccessible, these lives are on the line and protests erupt as a result.

Wait and Watch

At the time of writing and given the analysis above on these three fronts; great power competition, energy and economics, and food (in)security, the standard position of Arab governments is a cautious ‘wait and watch’ or one of “anticipation.” Few Arab governments have taken clear public positions or have offered to play a role in defusing tensions between Russia and the West. As many Arab analysts note, such a position is understandable, and perhaps even welcome as a temporary measure. However, there is a danger that lies in this ‘wait and watch’ position becoming a permanent response toward the situation, which may then pressure the Arab governments into choosing sides between America and its Western allies, and Russia, particularly if diplomacy fails and war breaks out. If social media activity is any indication, as other analysts have warned, the Arab street has already made clear its leanings toward Russia. Perhaps it is a mere snub to America in the region and the western world, as Russia stands firm in challenging its superpower status in Europe.

This Article Has Originally Been Published By Wilson Centre