Two visits during the Ukraine war: Geopolitical interests bringing Russia and Hamas closer

Ali Abo Rezeg[1]

When a Hamas delegation landed in Moscow last week, it marked the Palestinian group’s second high-profile visit to Russia since the Ukraine war began this February. Led by Hamas chief Ismail Haniyeh, the delegation arrived in the Russian capital just three months after a trip by Musa Abu Marzouk, the man in charge of the group’s international relations. The backdrop, evident urgency, and high level of these exchanges points to a mutual belief that there are shared interests to explore, and neither side wants to waste any time, hence the two visits within the space of just a few months.

The current understanding on mutual interests also marks a move away from Russia’s previous role as a great power balancing the US by forging relations with non-state actors, social movements in particular, that Washington has designated as terrorist entities. In the past, Russia’s ties with many of these groups were based almost exclusively on the idea of challenging US policies in the region.

This analysis seeks to understand the political developments brought about by the Ukraine war, which the Hamas leadership seems intent to capitalize on. It also discusses the dynamics that have pushed the two sides to strengthen their relationship, with Hamas presenting itself as a potential partner that could help protect Russia’s regional geopolitical interests.

The Ukraine war has revealed Moscow’s great geopolitical ambitions for the “post-unipolar world”, with a number of Russian officials, especially Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov,[2] reiterating that while the US and its Western allies are opposed to a multipolar world, “they will not be able to return to the unipolar system.” The vigorous participation of leaders from countries such as Russia, China, India, Pakistan, Turkey, and Iran in the recent Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit in Samarkand, Uzbekistan was a testament to Moscow’s endeavors to this end, with the summit portrayed as a major “rejection front” to the West. The SCO gathering saw Russia take the stage as a world power leading the charge for a new multipolar global order.

As for Hamas and Moscow’s growing shared interests, it all boils down to three points: strained ties between Russia and Israel over the Ukraine war, Israel’s ambition to replace Russia as Europe’s main gas supplier, and the soft power that Hamas enjoys in several countries within the Islamic world.

-Tension with Israel

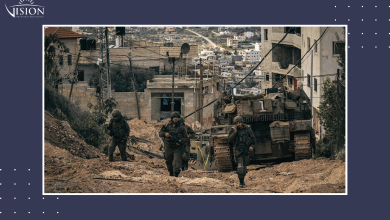

Firstly, improving relations with Hamas serves Russia in light of its mounting discord with Israel over the Ukraine crisis and the Syria situation. After Israel bombed different Syrian regime sites, Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov alluded to what he called “increasing chaos” in ties between Moscow and Tel Aviv. Russia also condemned Israel’s recent attack on Aleppo airport, calling for Syria’s “sovereignty and territorial integrity” to be respected. That was followed by the use of Russian anti-aircraft missiles against Israeli fighter jets that were on military missions near the cities of Masyaf and Latakia in northwestern Syria.

Though the missiles never posed a real threat to the aircraft, the incident clearly conveyed Moscow’s annoyance at Tel Aviv’s policies in Syria. The message was also the more direct given that the missile systems were under the control of Russian battalions and could not have been launched without Russian authorization. Not to mention that a Russian official at the Hmeimim Center Naval Brigade claimed, in statements to Russian news agency TASS, explicitly claimed responsibility for firing the missiles.

Israel’s condemnation of the Ukraine war is another bone of contention, as is Tel Aviv’s military aid to Kyiv – mostly in the form of low-tech defense equipment – and humanitarian assistance. The Russians also claim to have photographic evidence that dozens of Israeli military commanders were on the ground helping Ukrainian forces in Kherson and Kharkiv. Another sign of Moscow’s outrage at Tel Aviv’s stance on the Ukraine war is its unexpected push to close down the Jewish Agency for Israel’s branch in Russia. Moscow has started the process to expel the quasi-governmental organization, which promotes and facilitates immigration of Jews to Israel, accusing it of violating Russian laws.

Russia’s overtures with Hamas, a major player in the Palestinian equation, at such a time indicates the level of discontent between Moscow and Tel Aviv. It is also a good example of the nature of relations between major countries and non-state actors, most importantly social organizations. It highlights the need for superpowers to foster relationships with these actors to protect their own interests, be it by balancing power and exerting pressure on opponents, or taking advantage of these ties to avert potential threats. This is one of the most important aspects of the neo-realist (offensive realism) approach in international relations,[3] which Moscow has pursued with its expansionist policies since the Crimean crisis of 2014.[4]

– Europe’s energy crunch and Israel’s ambitions

It is in Russia’s interest to block, or even sabotage, Israel’s push to substitute Moscow as Europe’s main gas supplier. With Europe boycotting Russian gas as punishment for the Ukraine war, Tel Aviv has repeatedly said it wants to fill the gaping void, emphasizing that it will be ready to take over the role within a few years. Europe is keen to take up the offer, not just to overcome its crippling dependency on Russia, but also to foster a regional alliance between Israel and Egypt.

European officials have hinted that Egypt could be part of a permanent solution, as gas coming from Israel could be liquefied there at facilities that could soon be up and running. This will pave the way for Israeli gas exports to Europe, as well as generate immense investment opportunities and greater prospects for cooperation between Israel, Egypt, and Europe over the coming years. Europe’s pressing need for Israeli gas, along with the US effort to undermine Russia’s energy exports, can be seen in the Washington-led shuttle diplomacy over the disputed Karesh gas field that is claimed by both Lebanon and Israel.[5]

Having visited the region several times in recent months, US envoy Amos Hochstein said he is optimistic that an agreement to demarcate maritime borders is imminent. The US is clearly eager to resolve the issue, with an Axios report last month citing a White House official as saying that “resolving the maritime conflict between Israel and Lebanon is a major priority for the administration of Joe Biden.”

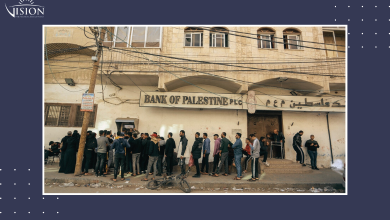

Hamas has positioned itself as a prominent actor in this situation, rejecting calls for any sort of regional cooperation in the field of energy, maintaining that such projects deprive Palestinians of the right to their own resources. This was the same contention put forward at protests in Gaza when the Hamas delegation was in Moscow, with charged Palestinians demanding their right to the gas that lies in fields just off the blockaded territory’s shores. Hamas’ military wing, known as the al-Qassam Brigades, also tried to target Israeli gas facilities during the last war with Tel Aviv in the summer of 2021. While they were largely unsuccessful, the attacks triggered serious concern among decision-makers in Israel, who fear that Hamas might have more accurate weapons that could inflict much greater damage.

Gas pipelines between Israel and Egypt were also the target of almost weekly attacks following the 2011 uprising in Egypt. Israel believes a Hamas with upgraded missile capabilities could be a serious threat to any possible regional cooperation on gas, endangering Tel Aviv’s push to take over Russia’s mantle as Europe’s go-to-guy.

– Hamas’ soft power

Hamas has conveyed to the Russian leadership the extent of its soft power and influence within the Muslim world in general, and the Muslim republics in the Russian Federation in particular. Moscow views its Muslim republics and their populations as a bridge with the Muslim world, and they were a key factor as Russia gained the status of an observer in the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) in 2005. This seems to be Moscow’s reasoning as it, for the first time ever, facilitated meetings between Hamas and leaders of the Muslim republics in the Russian Federation.

The visiting Hamas delegation met with Rustam Minnikhanov, leader of the Republic of Tatarstan, and Haniyeh congratulated him on the 1,100th anniversary of the Volga Bulgars’ conversion to Islam, while the region’s capital Kazan has been named the OIC Youth Capital for the current year.[6] Furthermore, Hamas presents itself as a movement with a strong following in the Muslim world, which is largely at the wrong end of today’s unipolar world and opposes the US’ blind support to Israel that has given Tel Aviv seemingly full impunity to violate the rights of Palestinians. To this end, it is worth mentioning that Hamas’ main statement to Russian officials affirmed that “the US global hegemony has harmed the Palestinian cause.”[7]

Hamas’ influence could serve Moscow in a new multipolar or bipolar world after the Ukraine war, if Russian estimates and predictions of the outcome of the war prove to be accurate.

– Conclusion

The geopolitical currents generated by the Ukraine war may push Russia to strengthen its relations with Palestinian groups in general and Hamas in particular. The most significant consequence has been the rift between Russia and Israel over the war, as well as Israel’s multiple attacks on Moscow’s Syrian allies. Hamas presents itself as a force opposing Israel’s plans to pursue regional energy projects that deprive Palestinians of their own natural resources. Hamas, with its soft power in the region and within the larger Muslim world, may prove useful for Russia in the post-Ukraine war world, which could reflect what Moscow has been seeking to establish since 2014.

Notes:

[1] Palestinian researcher. Holds PhD in international relations. Interested in Gulf and Palestinian studies.

[2] Russia says post-1991 ‘illusions’ about the West are over, Reuters.

[3] A school in international relations that highlights the role of power politics in the international relations, favours competition and conflict over cooperation and international society. Main theorists: Kenneth Waltz, the author of Theory of International Politics.

[4] Jacek Wieclawski, Contemporary Realism and the Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation.

[5] EU signs gas deal with Israel, Egypt in bid to ditch Russia, Al Jazeera.

[6] Haniyeh meets leader of the Republic of Tatarstan, Yeni Safak.

[7] Hamas Leaders Visiting Moscow To Russian Officials: We Are Entitled ‘To Resist Occupation By Every Possible Means’, MEMRI.