The Palestinian-Israeli conflict: Has the equation changed?

Throughout his term in office, the longest in Israeli history, Benjamin Netanyahu has sought to implement his expansionist vision regarding the Palestinian territories occupied in 1967. Netanyahu’s vision was explicitly articulated in the Nation-State Law, which declares that “the state views the development of Jewish settlement as a national value and will act to encourage and promote its establishment and consolidation.” The Israeli PM made his stance clear at the most recent U.N. General Assembly meeting in a speech that described such Palestinian demands as the right of return for refugees, Israeli withdrawal from the occupied Palestinian Territories, and the evacuation of Israeli settlers from the West Bank as unrealistic.

Netanyahu’s Palestine policy: building on (and breaking with) precedent

In the West Bank, Netanyahu has pursued a policy that undermines the Palestinian Authority (PA). While he has boycotted the PA politically and refused to negotiate with it, he has been more than happy to maintain security cooperation and financial dealings on terms favorable to Israel. To bury the two-state solution, Netanyahu has worked to keep Gaza and the West Bank under rival leaderships, stating publically that the split serves Israel’s strategy of making a future Palestinian state less likely. Simultaneously, Netanyahu has kept Gaza under a strict siege in order to clamp down on Hamas and force Gazans to live under precarious conditions. It is true that Netanyahu has allowed the flow of Qatari money into Gaza via Israel, but behind the alleged humanitarian motives lie pragmatic calculations by Israel.

Netanyahu’s vision, which draws upon past Israeli policies, is of course not new. Since the occupation of the Palestinian Territories began in 1967, Israel has sought to colonize and annex as much land as possible. But Netanyahu has exhibited an animosity toward the political aims of Palestinians — and an unwillingness to negotiate with them — rarely matched by any of his predecessors. In 1993, the Yitzhak Rabin government (1992-95) signed the “Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements,” better known as the Oslo 1 Accord. This agreement granted the PLO semi-autonomy and called for a resolution of “permanent status” issues, such as borders, the right of return, and sovereignty over Jerusalem within 5 years. Netanyahu first became PM in 1996, the year after Rabin’s assassination. During his three-year stint, he balked at implementing the provisions of the agreement. Successive governments were more accommodating, as PM Ehud Barak (1999-2001) negotiated with the Palestinians at the U.S.-sponsored Camp David talks and PM Ariel Sharon withdrew Israeli soldiers and settlers from Gaza.

PM Ehud Olmert (2006-09), negotiating with PA President Mahmoud Abbas, almost made a breakthrough, but his progress was halted when corruption charges forced him to resign and led to elections that reinstalled Netanyahu in power. Despite blandishments from the Obama Administration, Netanyahu refused to accept previously signed agreements as the framework for negotiations. Netanyahu is unlike other recent Israeli PMs, who at least sat for negotiations and paid lip service to the two-state solution, even as they expanded settlements. Only once — in a 2009 speech at Bar Elan University — did he express support for the two-state solution, support that he later retracted. Statements and decisions made by Netanyahu throughout his tenure make evident his fervent desire to replace decades of signed agreements with his own vision. It was this same vision that was reflected in President Donald Trump’s so-called “Deal of the Century,” which was designed to satisfy Netanyahu rather than offer a viable roadmap for a just peace.

Israel in the broader region

With the Arab Spring revolutions of 2010-11, a new regional dynamic began to emerge. Attention was diverted away from the issue of Palestine as major Arab powers, particularly Egypt and Syria, became preoccupied with their own internal problems. These two countries could no longer play any practically significant role in supporting the Palestinians and gave Israel free rein in the occupied territories. Egypt also agreed to contain Hamas in return for Israel’s help in fighting against ISIS-affiliated insurgents in Sinai. This is but one example of how Arab countries have been putting security aid from Israel above solidarity with the Palestinians.

Further east, the Iranian threat against the Arab Gulf states was emphasized in various quarters, driving them closer first to the United States and then to Israel as well. To ensure American and Israeli support and protection, these Gulf states had to turn a blind eye to Israel’s aggressive policies towards the Palestinians. Along with pressure by President Trump, these developments created the conditions for the latest wave of Arab states’ normalization agreements with Israel, including those already signed by the UAE and Bahrain as well as those yet to come, such as Sudan.

Israel has long sought to separate the Palestinian cause from its Arab context. Netanyahu considered the recent normalization agreements as a way to end the Palestinian veto over broader Arab-Israeli relations. Normalization clearly means diminished Arab support for the Palestinians in their struggle with Israel.The formula for Palestinian-Israeli peace, which is explicitly endorsed in the Arab Peace Initiative of 2002 and which is based on the “Land for Peace” formula enshrined in UN Security Council Resolution 242, has been rendered obsolete by Arab states’ normalization with Israel.

Netanyahu has succeeded in adding new factors to the Palestinian-Israeli equation that may allow Israel to make greater demands and extract greater concessions from the Palestinians in future negotiations. Perhaps no future Israeli leader will be able to challenge or reverse what Netanyahu has done, particularly in light of Israeli society’s clear drift to the right. Furthermore, some Arab countries have come to terms with these changes in the Palestinian-Israeli arena and adapted their approach to the Palestinian question accordingly.

The only factor that could obstruct Netanyahu’s strategy and Israeli efforts to further change the parameters of the conflict is the Palestinians themselves. The options for the Palestinians at this point in time look limited. Still, they may take comfort in the knowledge that throughout this century-old conflict they have been through equally bad, if not worse, times. Another source of solace is the broad support their cause still enjoys worldwide as well as the hope that circumstances in the region and elsewhere will change in their favor. For example, Joe Biden is likely to discard Trump’s Deal of the Century and reestablish normal relations with the Palestinians. Finally, the last option for the Palestinians, if the two-state solution becomes unviable, is to advocate for a one-state solution. Facing the undesired possibility of a one-state scenario, Israel might at last change its policies.

The Israeli government is trying hard to pressure the Palestinians politically and financially, and this pressure is unlikely to vanish anytime soon, especially if Netanyahu stays in power. Although it has not done so officially, Israel has gone back upon its previously signed agreements, and insists on making the Deal of the Century the only framework for resolving the question of Palestine. The Israeli government suspended its annexation plan, but could implement it at some time in the future. Financially, Israel alone decides how much tax money is transferred to the Palestinian Authority (PA), and it unilaterally holds back funds under different pretexts. The U.S., for its part, has stopped financial support to the Palestinians and pressured the Arab countries to cut off financial support to the PA, which is undergoing a dire financial crisis.

Netanyahu successfully exploits changes in the Palestinian-Israeli relationship and in the Middle East at large to consolidate his domestic political position despite his problems and failures. His hard-line stance on Palestine, along with his diplomatic advances in the broader Middle East, has helped keep him and his Likud party at the top of Israeli politics despite a spate of domestic crises. Most Israelis support the annexation plan and the normalization agreements with the UAE and Bahrain. And although Likud’s power has declined somewhat, it continues to enjoy strong support in the polls. Netanyahu remains the “best suited” to be prime minister in the eyes of the Israeli public, ahead of Yair Lapid, Naftali Bennett, or Benny Gantz. Significantly, Naftali Bennett, who outflanks Netanyahu from the right, has recently enjoyed an uptick in support at the expense of the sitting PM.

Even amid the spread of the coronavirus and corruption allegations, Netanyahu has largely held on to his popularity. Tightening the Israeli hold over the occupied territories is not only an ideological objective, but also an effective strategy for cementing the electoral support of right-wing voters. This is why he recently announced his intention to build thousands of new settlement units in the West Bank, which will have lasting political and demographic consequences. The longer Netanyahu stays in power, the more his worldview become ingrained as a durable paradigm for Israel-Palestine relations. Thus, Israeli policies towards the Palestinians regarding settlement building and the peace process are not at all likely to change, even once Netanyahu leaves office.

Sania Faisal El-Husseini is a Professor of International Relations at the Arab-American University in Palestine, and a writer and researcher who has published numerous political articles and research papers. El-Husseini worked with the Palestinian National Authority for more than two decades in information and diplomatic roles. The views expressed in this piece are her own.

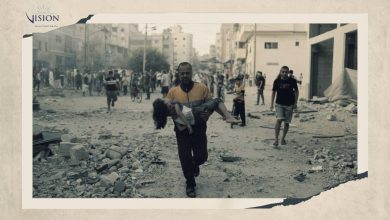

Photo by Abbas Momani/AFP via Getty Images

This article was originally published on the Middle East Institute