The Ibrahimi Mosque After October 7: From Occupation to Judaization

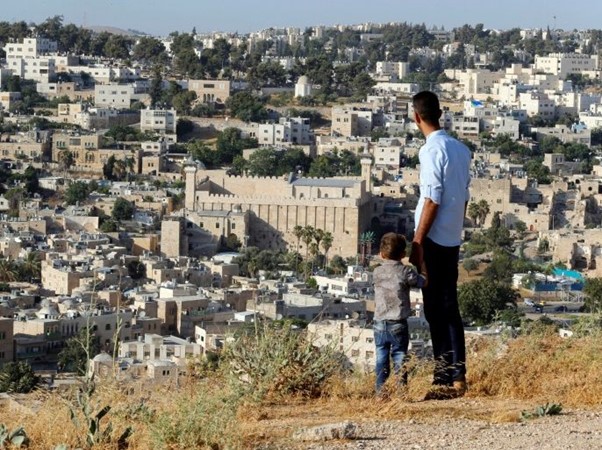

Perched atop one of Hebron’s commanding hills, the view is nothing short of arresting. There, at the heart of the ancient city, rises a monumental structure — the Ibrahimi Mosque. Majestic, sacred, and steeped in millennia of history, it stands as both anchor and witness to Hebron’s turbulent past. Around it, a dense mosaic of timeworn grey stone-homes clings to the slopes, as if the old city itself bends in solemn reverence, silently guarding the prophets’ sanctuary. This is no ordinary monument — it is a battleground of memory, faith, and power, a living testament to Hebron’s contested soul.

In the aftermath of October 7, the Ibrahimi Mosque — already a focal point of tension — now stands at the intersection of two relentless forces: deepening occupation and accelerating Judaization. What was once a symbol of shared sacredness has increasingly become a space of exclusion, militarization, and control.

The Israeli state, emboldened by the shifting political winds and securitized narratives post-October 7, has intensified its grip on Hebron’s Old City. Checkpoints multiply. Access is rationed. Worship is regulated. The very stones of the mosque — soaked in centuries of reverence — now echo with the weight of demographic re-engineering.

Since the Occupation of Hebron and the Establishment of the Kiryat Arba Settlement — the Largest in the Area — the Ibrahimi Mosque Has Become the Epicenter of a Systematic Settler-Colonial Project.

Nowhere has this been more brutally manifest than in the 1994 Ibrahimi Mosque massacre. That atrocity was not a fleeting act of violence — it was a political rupture. It redefined the relationship between Palestinians, particularly the people of Hebron, and their sacred spaces.

In its wake, a new vocabulary took root: fear, resilience, belonging. For the residents of Hebron, access to the mosque became not just a matter of faith, but a daily confrontation with occupation.

This article examines Israel’s intensified push towards the Judaization of the Ibrahimi Mosque in Hebron following October 7, 2023 — a calculated escalation marked by tighter control, new policies, and a systematic erasure of the site’s Palestinian identity in time, space, and architecture.

What we are witnessing is not merely administrative tightening or enhanced “security” measures — it is a deliberate campaign to reshape the sacred landscape. Through increasingly restrictive access, architectural interventions, and the redefinition of religious and civic space, the occupation seeks to reimagine the Ibrahimi Mosque not as a shared or sacred Palestinian site, but as a symbol of domination, exclusion, and irreversible change.

Prelude to Control: The Pre-Partition Years

Israel’s stranglehold on Hebron did not begin with the 1994 massacre — it was decades in the making. In October 1968, just a year after occupying the West Bank, the Israeli government approved the establishment of Kiryat Arba on the eastern edge of Hebron — a settlement that quickly became the ideological nerve center of the radical religious settler movement.

From that point forward, Israeli authorities moved step by step to assert control over the Ibrahimi Mosque. What began with quiet, unofficial Jewish prayers inside the mosque soon evolved into formal appropriation.

In 1976, the section that is known as the “Great Hall” was carved out and turned into a military outpost, even though it contained a mihrab for Muslims, in a first step towards turning it into a semi-permanent synagogue. On 2 November 1983, settlers brought in tables and chairs in the Hall, effectively transforming the space into a de facto yeshiva, a Jewish religious school.

The Temple Mount has also witnessed repeated incursions, most notably on 28 February 1972, when Meir Kahane, the leader of the extremist Kach movement, stormed it. On 4 June 1991, settlers brought a worship table into the Jacobite shrine, started giving religious lessons, and prevented Muslim female students from passing through it.

These policies culminated in the February 1994 massacre perpetrated by settler Baruch Goldstein, which resulted in the de facto division of the Temple Mount between Muslims and settlers, under the pretext of “security.”

A Settler Project Unlike Any Other: Reshaping Hebron from Its Core

The attacks on the Ibrahimi Mosque did not occur in isolation — they are part of a broader, uniquely aggressive settler strategy that targets the heart of Hebron itself. Unlike the typical pattern of West Bank settlement, which expands outward along hilltops and peripheries, the Hebron model is surgical and symbolic: to embed control at the center. This is a calculated Israeli effort to assert dominance over the Ibrahimi Mosque and to impose a new demographic and security reality on the city.

Three key milestones mark the tightening grip:

– In 1968, settlers seized the Park Hotel — their first foothold inside Hebron’s urban fabric.

– In 1979, settlers reoccupied the Beit Hadassah building (known locally as Al-Dabuya), deepening their presence in the Old City.

– In 1984, settlers took over Beit Romano and converted it into a Jewish religious seminary under heavy military protection.

Together, through these moves, a tight settlement cordon was established around the Ibrahimi Mosque, transforming the city into a religious and military centre that reflects the occupation’s will to change the city’s identity and reshape it according to the logic of hegemony and control.

Spatial and Temporal Partition: Post-Massacre Control of the Ibrahimi Mosque

On February 25, 1994, during dawn prayers in the Ibrahimi Mosque, settler Baruch Goldstein opened fire, killing 29 Palestinian worshippers and injuring dozens more in one of the most brutal episodes of settler violence under military occupation. Following the massacre, the Israeli government formed a committee headed by Justice Meir Shamgar which recommended dividing the Temple Mount in a so-called “separation” between Muslims and Jews — a decision that laid the groundwork for a formal spatial and temporal partition of the site.

On 25 February 1994, settler Baruch Goldstein committed a massacre inside the Temple Mount during morning prayers, killing 29 Palestinians and injuring dozens more. Following the massacre, the Israeli government formed a committee headed by Judge Meir Shamgar, which recommended dividing the Temple Mount, citing the separation of the two sides.

Under this imposed division, Muslims were confined to the southern half of the mosque — the Ishaqiya prayer hall — the mosque’s largest and holiest section, home to Salah al-Din Ayoubi’s pulpit, the mihrab, the sacred chamber, and the tombs of the Prophet Ibrahim and his wife Sarah (according to Islamic tradition). They were also granted access to the Jawliyah prayer space — an outdoor women’s area built in 1312 CE by Mamluk commander Sanjar al-Jawli, characterized by distinctly Islamic architecture unlike the interiors of the mosque itself.

Meanwhile, settlers took over the central courtyard and converted the Ibrahimi, Yaqoubi, and Yousufi (Abrahamic, Jacobite and Josephite) chapels into Jewish prayer spaces, all guarded by a permanent and heavily armed Israeli military presence.

In this manner the sacred space was redrawn. What followed was not reconciliation, but reconfiguration: a centuries-old Muslim sanctuary fractured, militarized, and occupied.

A Sacred Site Behind Barriers: The Militarized Reality of the Ibrahimi Mosque

Worship at the Ibrahimi Mosque no longer begins with ablution or the call to prayer — it begins with checkpoints, guns, and metal detectors.

Since the outbreak of the Second Intifada in 2000, access to one of Islam’s holiest sites has come to resemble entry into a locked-down military zone. Israeli authorities have banned the entry of prayer books, loudspeakers, and even basic cleaning supplies. Any repair work requires prior approval, and control of the site has been handed over to Israeli police.

Approaching the mosque today is an ordeal. The first sign of restriction is a steel gate that severs Hebron’s Old City from its natural continuity. It is followed by a gauntlet of barriers — each one ratcheting up the sense of suffocation. The initial checkpoint is often a mobile military post, staffed by heavily armed soldiers who scrutinize every face and demand IDs.

Then comes the primary barrier: a narrow electronic turnstile that locals have come to call “the chicken coop” — a humiliating nickname born not of poetry but of painful precision. No more than two people can pass at a time. Surveillance cameras watch every move.

Overseeing it all are Israeli commanders stationed in a building adjacent to the mosque, where they control entry, prayer times, and closure schedules with bureaucratic coldness.

Surrounding streets like Souq al-Laban and Souq al-Hisba are either entirely sealed or forcibly emptied — shops rusted shut, doors padlocked under military orders. Above them, settlers now reside, guarded by soldiers, peering down from rooftops onto a city being suffocated into silence. What was once a vibrant religious and commercial hub has been transformed into a fortified shadow — a besieged sacred space.

Violation of the Spatial and Temporal Boundaries

After 7 October 2023, the occupation authorities intensified their projects inside the Ibrahimi Mosque, taking advantage of the state of emergency to impose new realities.

In 2023 alone, the call to prayer (adhan) at the Ibrahimi Mosque was silenced 704 times — a staggering, unprecedented figure. Many of these bans occurred during time slots officially designated for Muslim worship under the post-massacre division agreement. The stated justifications? Vague “security concerns” or claims that the adhan “disturbs settlers.”

The violations extended far beyond prayer calls. Worshippers were barred from entering the mosque during their own religious holidays, including Eid al-Adha and Laylat al-Qadr — sacred days clearly classified as “Muslim days” by the original division framework. Even the eastern gate, traditionally opened for Islamic festivals, was sealed without legal justification, cutting off a vital access point.

On the spatial front, the erosion has been just as stark. Large sections of the mosque have been effectively converted into exclusive Jewish spaces. Muslims are denied entry to these areas — even on days allocated to them. Islamic Waqf offices inside the mosque, including the adhan room and staff quarters, have been forcibly shut. The director of the mosque, Sheikh Mu’taz Abu Sneineh, was detained — a symbolic blow aimed at undermining the Islamic custodianship of the site.

What we are witnessing is not simply a breach of an already-unjust arrangement. It is the systematic dismantling of Palestinian religious presence — a slow-motion annexation, executed under the banner of “security,” but rooted in a deeper logic of domination and dispossession.

Crippling the Waqf: A Targeted Campaign Against Islamic Custodianship

Since October 7, 2023, Israeli authorities have tightened their grip on the Ibrahimi Mosque by systematically restricting the work of Islamic Waqf staff — a calculated move to dismantle Palestinian religious oversight and impose full Israeli security control over the site.

Routine maintenance and cleaning — tasks as simple as fixing a light or sweeping a courtyard — now require prior “security coordination,” turning basic upkeep into a bureaucratic maze and a political tool of coercion. The delays are deliberate, the message unmistakable: authority at the site no longer rests with its rightful custodians.

According to Jamal Abu Aram, Director of the Waqf in Hebron, Israeli forces have padlocked and chained shut most of the doors within the Muslim section of the mosque, including staff offices and the adhan room — a dangerous precedent that paralyzes daily operations.

Even during major Islamic holidays like Eid al-Adha and Ramadan, Israeli authorities refused to hand over the mosque’s keys to Waqf employees — denying them access to administer sacred observances. This was no oversight; it was strategy.

Further tightening the noose, occupation forces have launched a wave of interrogations and arrests targeting Waqf staff, including the detention of mosque director Sheikh Mu’taz Abu Sneineh. IDs have been confiscated, staff harassed, and offices searched under constant surveillance.

Worship Under Siege: Lockdowns, Strip Searches, and Denial of Entry

Israeli authorities have turned access to the Ibrahimi Mosque into an ordeal of humiliation and obstruction, particularly since October 7, 2023. A permanent military post now stands at the mosque’s gates, enforcing invasive security checks on every worshipper — including full-body searches, bag inspections, and ID verifications.

This regime of control is especially punishing during Fajr (dawn) and Friday prayers, when restrictions are heaviest and the spiritual stakes highest. Hundreds of worshippers are regularly turned away, forced to pray outside the gates in harsh conditions — not because of lack of space, but because of a deliberate policy of exclusion.

Inside the mosque, access is no easier. Israeli forces have arbitrarily sealed interior doors and imposed random, unpredictable limits on prayer times. Worshippers often arrive only to find entrances suddenly shut or to be detained for hours under the pretext of “temporary security measures” — measures that have become, in practice, permanent violations of the agreed spatial and temporal division.

The result is a climate of exhaustion and degradation. Prayer becomes a test of endurance. The right to worship — already fragmented by occupation — is further fractured by a system designed not to protect, but to dominate.

Eroding Heritage: Architectural Defacement and the Seizure of Surrounding Properties

Since 2021, Israeli authorities have launched a systematic effort to distort the historic character of the Ibrahimi Mosque — a campaign cloaked in bureaucratic language but driven by political intent. At the center of this effort is the controversial construction of an electric elevator within the mosque’s courtyard, spanning nearly 300 square meters and funded by a government budget of 2 million shekels.

Marketed as an accessibility project for people with disabilities, the move has been fiercely opposed by the Palestinian Ministry of Religious Endowments and local heritage organizations, who view it as a blatant assault on the site’s Islamic architectural identity. Far from a neutral infrastructure upgrade, the elevator is widely seen as a wedge — a means to expand settler presence and alter the spatial dynamics of the sacred complex under the guise of inclusion.

This is not merely a construction project — it’s an act of spatial appropriation. By inserting modern, foreign structures into a centuries-old Islamic site, Israeli authorities are not just violating architectural integrity; they are redrawing the lines of control.

What unfolds is a dual strategy: the physical fragmentation of the mosque from its urban context and the symbolic fragmentation of its identity — a process where “renovation” becomes colonization, and “accessibility” masks annexation.

Architectural Judaization: The Attempt to Alter the Heart of the Ibrahimi Mosque

Among the most alarming manifestations of architectural Judaization in recent years was the Israeli attempt to cover the open-air courtyard between the Ibrahimi and Yaqoubi halls within the Ibrahimi Mosque — a move that Palestinians saw not only as physical interference, but as a deliberate distortion of the site’s historic and spiritual fabric.

The proposed installation of a permanent metal roof was met with firm Palestinian rejection. Heritage experts, religious authorities, and local residents denounced it as an act of architectural vandalism — a violation of the mosque’s original structure and a breach of the post-massacre Shamgar Commission agreement, which allowed for spatial division but explicitly prohibited alterations to the mosque’s core features.

The outcry in Hebron was swift and vocal. Public protests, official condemnations, and grassroots mobilization forced Israeli authorities to temporarily shelve the plan — a rare pause in a broader pattern of unilateral changes.

In a stark escalation, Israeli authorities have reportedly proceeded with the closure of the central courtyard within the Ibrahimi Mosque, covering it with corrugated metal sheets — a move widely circulated on social media and condemned by Palestinians as a blatant act of architectural and religious violation.

Flags, Fortresses, and the Fading Cityscape: Rewriting Hebron’s Visual Identity

In recent months, Israeli flags have become a common sight atop buildings surrounding the Ibrahimi Mosque — not as incidental gestures, but as markers of dominance. These symbols now loom over a site sacred to Muslims, signalling a shift not just in power, but in narrative.

The military presence has also expanded. What was once a checkpoint has morphed into a permanent surveillance base, reinforcing the sense that this is no longer a protected holy site, but an occupied zone under constant watch.

Nearby buildings have been seized and partially converted into Jewish religious and tourist centers — a creeping transformation that recasts the area’s character. These changes go beyond architecture; they rewrite meaning. The historic Palestinian core of Hebron is slowly being overlaid with a settler aesthetic — a spatial rebranding designed to shift how the city is seen, experienced, and remembered.

This is not just urban change — it is strategic erasure. The old city’s heart is being redrawn, not with maps, but with flags, cameras, and stone.

In a deeply provocative move, Israeli forces hoisted the national flag directly on the facade of the Ibrahimi Mosque — a sacred Islamic site and flashpoint of contested sovereignty in Hebron’s Old City. Captured on September 23, 2024, the image spread widely, igniting outrage across Palestinian communities and beyond.

What some frame as symbolism, others see as declaration: a flag not just marking presence, but asserting control — over space, over history, and over meaning.

Amid Judaization and Siege, Hebron’s Community Holds the Line

Despite the creeping Judaization and suffocating daily restrictions, Hebron’s local community remains the first and most resilient line of defense for the Ibrahimi Mosque. In the face of military checkpoints, denied access, and structural erasure, residents have turned worship into resistance.

One of the most powerful grassroots responses is the “Great Fajr Campaign” — launched by local families to revive collective dawn and Friday prayers at the mosque. Especially on days of closure or heightened military presence, these gatherings transform prayer into an act of civil defiance.

More than ritual, it is presence with purpose — a reminder that the mosque’s identity is not up for negotiation, and that the community’s bond with it runs deeper than occupation’s barriers. In Hebron, faith is not just practiced — it is defended.

Architecture as Resistance: Hebron’s Reconstruction Committee and the Defense of Heritage

Parallel to the popular defiance on the ground, the Hebron Rehabilitation Committee (HRC) plays a critical role in protecting the Ibrahimi Mosque and fortifying Palestinian resilience in the Old City. Its work goes beyond preservation — it is a strategic, daily act of resistance through restoration.

From repairing doors and windows of the mosque to restoring homes damaged by settler violence and military-enforced isolation, the Committee’s projects sustain the fabric — both physical and social — of a city under siege. Backed by international partners such as the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TIKA)[1] and the Arab Fund, these efforts ensure that Hebron’s Old City does not crumble under pressure. Equally vital is the Committee’s support for daily Palestinian presence. By keeping staff and residents anchored in place, and offering legal aid to those facing settler harassment or army incursions, the HRC acts as a frontline institution — not just preserving stones, but protecting sovereignty; making its work an extension of the architectural and administrative defence line for the Haram and the Old City[2].

In a city where control is fought street by street and wall by wall, the Hebron Rehabilitation Committee has become a steadfast architectural and administrative shield — defending memory, identity, and the right to remain.

The Ibrahimi Mosque is no longer just an Islamic religious landmark, but a daily confrontation between a systematic Judaization project and a Palestinian presence that seeks to preserve its religious and historical right. Since the occupation of Hebron, the occupation authorities have been pursuing accumulated policies aimed at establishing spatial and temporal control over the Haram, from dividing it after the 1994 massacre, to the exceptional measures that intensified after 7 October 2023, from banning worshippers and the call to prayer, to restricting endowments, and defacing architectural features.

These policies are not an exception, but a clear manifestation of the occupation’s approach throughout the West Bank, where war and security are used as a pretext to reshape place, identity, and sovereignty in a way that serves the colonialist narrative and undermines the Palestinian presence.

[1] TIKA is a governmental organisation under the Presidency of the Republic of Turkey that implements development and foreign aid projects and works in dozens of countries around the world, including Palestine. TIKA oversees projects that restore infrastructure, historical monuments, mosques, and support community organisations. In Hebron, TIKA has carried out various restoration works in and around the Ibrahimi Mosque, including repairing doors and windows and restoring houses damaged by the isolation policy, the wall and checkpoints.

[2] Interview with Muhannad al-Jaabari, Director of the Ibrahimi Mosque Reconstruction Committee, Hebron, May 2025.

NOTE: This text is adapted from original Arabic article.