Once Again, Israel Throws Up an Unlawful Barrier to Palestinian Family Reunification

# Carol Daniel Kasbari | Middle East Institute

On March 10, Israel’s parliament enacted a bill denying naturalization to Palestinians from the occupied West Bank and Gaza who marry Israeli citizens. This legislation superseded a similar interim order approved in 2003 in the midst of the Palestinian uprising and reaffirmed annually until it expired in July 2021. While most foreign nationals who marry Israelis can live in Israel and eventually become citizens, Palestinians and certain other Arabs cannot. The law bars the unification of Israeli citizens or residents and spouses from “enemy states,” such as Lebanon, Syria, and Iran. But it mostly affects Palestinian women and children. Last summer, the Knesset failed to adopt the law because it lacked support from the governing coalition’s left-wing and Arab members. The opposition, led by former Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, supports the bill but did not vote on it in July in order to embarrass the government. However, this time around Interior Minister Ayelet Shaked, of Naftali Bennett’s far-right Yamina Party, worked tirelessly to guarantee the outcome of the vote along both coalition and opposition lines, resulting in just 15 members of the 120-member Knesset voting against the renewed one-year extension. While Labor abstained from voting, only the two Arab parties (Ra’am and the Joint List) and Meretz voted against it.

Shaked and other officials have admitted that the bill is primarily motivated by the desire to preserve Israel’s Jewish majority. A month before the vote, on Feb. 9, the interior minister made her intentions clear in an interview to the Yedioth Ahronoth newspaper, saying, “We don’t need to mince words, the law also has demographic reasons.” Shaked added, “The law wants to reduce the motivation for immigration to Israel. Primarily for security reasons, and then also for demographic reasons.” It is intended, she said, to prevent a “creeping right of return.”

The bill’s backers also defend it on security grounds, claiming that Palestinian militants may utilize marriage to gain entry into Israel. According to the Shin Bet, Israel’s internal security agency, however, “No one who has been allowed family reunification since the beginning of 2018 has helped plan or carry out a terrorist attack, but several of their descendants have; the agency deems six people as ‘assailants,’ five as ‘involved,’ and three as ‘accomplices.’”

Meanwhile, no one in Israel was surprised that this legislation would succeed, given that all Zionist parties, regardless of affiliation, believe that Israel is exclusively a Jewish state, and Israeli authorities occasionally acknowledge publicly, as Shaked did, that demographic factors are at the heart of this legislation. For instance, Foreign Minister Yair Lapid admitted last July, “We shouldn’t hide the essence of the Citizenship Law. It’s one of the tools aimed at ensuring a Jewish majority in the State of Israel.” In reality, demographics have been central to the law since its inception in 2003, all the way up to the Supreme Court verdict maintaining it in 2012.

Indeed, Shaked celebrated the passage of the legislation on March 10 by tweeting that it was a victory for “a Jewish and democratic state” and a defeat for “a state for all its citizens.” The latter expression is commonly used by Israel’s Palestinian citizens, who account for 21% of the population, to emphasize their desire for civil and national equality. Nevertheless, the regulation does not apply to the West Bank’s roughly 500,000 illegal Jewish residents, who live in the “hostile areas” and have Israeli citizenship. Thus, this law best exemplifies the ascendancy of Jewish supremacism in Israel, making it a Jewish rather than a democratic state.

Most Palestinians view the policy as yet another racially driven and discriminatory law that is, as Amnesty International put it in a February 2022 report, part of an apartheid regime whereby “Palestinians are treated as an inferior racial group and systematically deprived of their rights.” According to Israeli journalist Gideon Levy, “This law is definitive proof of the fact that not only are there apartheid practices in this country, there are apartheid laws here as well. “It’s best not to avoid the truth: Its existence in the lawbooks makes Israel an apartheid state,” wrote Haaretzpublisher Amos Schocken in 2008.

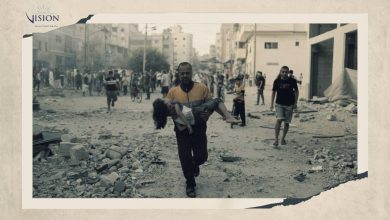

This has been a living nightmare for tens of thousands of Palestinian families both inside and outside the Green Line, including my own. For 15 years, from 1998 to 2013, I had to live a temporary life with my West Bank-born Palestinian spouse since he could not obtain residence to live with me in Jerusalem. He was unable to establish a bank account, operate a car, rent or buy a house or other property, or even travel freely between his family’s home in Ramallah and Israel or East Jerusalem. In 2000, during the latter weeks of my pregnancy, I stayed at my parent’s house in Nazareth to get their support. When I first went into labor, I contacted my husband, whom I hadn’t seen in weeks due to his inability to enter Israel without a permit. He was forced to travel for nearly a full day from Ramallah to Nazareth, rather than the three hours it would normally take. It was a bitterly cold December journey, parts of which were by foot, and required illegally crossing the Green Line. As he did so, he was terrified of being confronted or shot at by Israeli soldiers. Throughout the day-long journey all he wanted was to avoid missing my delivery and witnessing the birth of his firstborn.

In truth, the family reunion law is just one of dozens of Israeli regulations that discriminate against people based on their race, ethnicity, language, or origin. But even among these it is one of the most discriminatory laws aimed at Palestinian families — a racist violation of fundamental constitutional rights. It stops families and children from reuniting and enjoying normal lives and prevents Palestinians from choosing the love of their lives, from living where they wish, and even from travelling freely across cities and villages. In the words of Reut Shaer, an attorney with the Association of Civil Rights in Israel, “It comes off as more xenophobic or racist (than other laws) since it not only gives extra rights and privileges to Jews, but also denies certain basic rights to the Arab population.”

The good news is that several rights groups, including Adalah, have indicated that they will challenge the law before Israel’s Supreme Court. If that does not work, affected Palestinian families could decide to petition against it one by one, clogging the judicial system and making the situation untenable for Israel in the long term. This law will not prevent Palestinians from reaching their full human potential. It will not prevent them from falling in love with and marrying someone from across the border; from having two weddings, one in the West Bank and one inside the Green Line, as I did in 1998; or from living separately while collaborating to raise their children across boundaries. In the end, the affected Palestinian families, like Palestinians elsewhere, are unlikely to relinquish or surrender their rights without a fight — a reality successive Israeli governments have thus far failed to grasp.

This Article Has Been Originally Published by the Middle East Institute