Occupation’s Re-engineering of Northern West Bank: Destruction, Dismantlement, Displacement, Erasure

Toqa Hanun

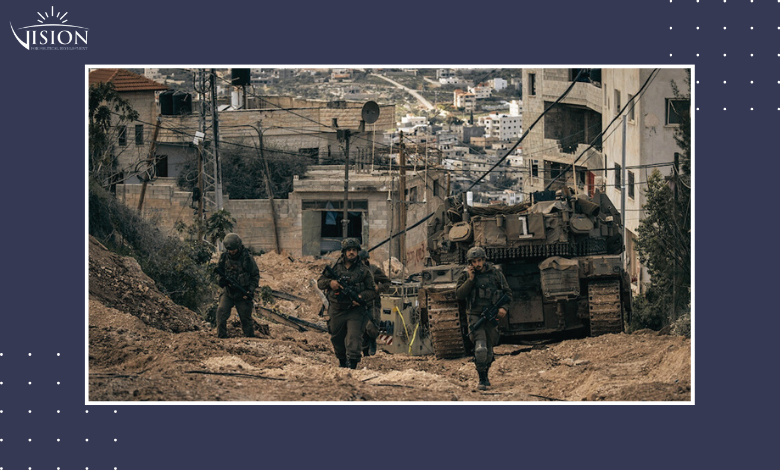

Since the Israeli army launched its assault on Jenin refugee camp under the banner of “Operation Iron Wall” on January 21st of this year—just two days after the Gaza ceasefire took effect—it has redirected its military might toward the northern West Bank, targeting the cities of Jenin, Tulkarem, Tubas, and Nablus. The brunt of its aggression has focused on their refugee camps: Jenin, Tulkarem and Nour Shams, Far’a, Ein Beit al-Ma’ (Ain), and Balata. The onslaught on Jenin and Tulkarem persisted for weeks, during which Israel occupied their camps, instigating the largest internal displacement in the West Bank since 1967.

Although most of the displacement remained within the urban peripheries and surrounding villages, the scope and intensity of the military campaign sparked urgent questions about the fate of the displaced and the future of the camps themselves. The invasion marked the most extensive campaign of collective demolition in the West Bank since the Second Intifada, and specifically since the 2002 siege of Jenin during “Operation Defensive Shield.”

The Israeli army began a systematic operation to evacuate the refugee camps and surrounding strategic areas, forcibly expelling residents through direct orders under threat of arms, indiscriminate gunfire, and deliberate deprivation—cutting off water, food, and electricity supplies. These tactics triggered successive waves of displacement, fully depopulating the Jenin and Tulkarem camps and driving the majority out of Nour Shams camp. According to UNRWA, the number of displaced persons exceeded 41,000[1].

This mass exodus unfolded under harsh winter conditions, forcing families to seek refuge in relatives’ homes, temporary shelters such as clubs, wedding halls, tents, and unfinished buildings. Hundreds of families were compelled to rent unfurnished housing, significantly increasing the burden of displacement. Many attempted to return to their homes multiple times, only to be expelled again during renewed Israeli incursions.

Displacement Patterns and Living Conditions

Over the past two and a half years, Israel’s repeated incursions into the Jenin, Tulkarem, and Nour Shams camps have caused devastating human and material losses. According to the Shireen Observatory[2], more than 500 Palestinians have been killed in the two cities and their camps. The infrastructure of the camps has been systematically destroyed, rendering them “disaster zones unfit for human habitation,” as described by their local popular committees.

While previous assaults had already triggered waves of both temporary and permanent displacement, the current invasion has led to the complete depopulation of these camps.

According to the Jenin Camp Popular Services Committee and UNRWA, over 18,000 people have been displaced from the camp and surrounding areas. These displaced residents are now spread across 86 locations, with the largest concentration in the city of Jenin itself. Around 1,300 families are currently renting private accommodations there, while approximately 520 families have taken refuge in student housing near the Arab American University—most of which is funded by the Popular Committee.

The remaining displaced families are dispersed across 84 sites in the villages surrounding Jenin, with the largest groups in Burqin, Qabatiya, Ya’bad, Yamun, and Silat al-Harithiya. Additionally, two villages in the Nablus governorate are also hosting displaced families[3].

In Tulkarem, atleast 13,500 people were displaced from Tulkarem Camp, along with approximately 9,500 from Nour Shams, according to UNRWA. These displaced residents have scattered across a wide range of population centers—from areas adjacent to the camps to neighborhoods and suburbs throughout the city. The majority have concentrated in the eastern and northern districts, as well as the outlying areas of Dhinnaba, Shuweika, al-‘Azab, Iktaba, and towns such as Bal’a, Attil, Anabta, and the Kufriyat cluster—dispersed across at least 40 residential areas.

The spontaneous, uncoordinated nature of the displacement, with no prior planning to manage the crisis or mechanisms in place to track population movement and distribution, has made it difficult for UNRWA and local committees to accurately assess the number and locations of the displaced.

The displaced refugees have borne immense financial and psychological hardship in their efforts to protect their families and children—particularly as the first waves of displacement coincided with the harsh winter and widespread unemployment and lack of income. The stranglehold of the Israeli invasion extended across both cities, where occupation forces pursued displaced individuals, arresting, detaining, or interrogating them even in their places of refuge.

Many families were displaced multiple times after receiving military evacuation notices for the very neighbourhoods they had fled to—especially in Tulkarem’s eastern and northern districts and Jenin’s al-Zahraa neighbourhood. These areas initially hosted hundreds of families from the camps, who had rented apartments and homes there, only to be forced out again under renewed threats and orders from the occupation.

Evacuation orders for dozens of residential buildings in neighbourhoods adjacent to the camps further deepened the displacement crisis. Many non-refugee civilians suddenly found themselves forced out of their homes, as Israeli forces stormed buildings and ordered immediate evacuation—sometimes giving as little as five minutes’ notice. Even the most “fortunate” were granted no more than ten hours to leave.

These raids and evacuation orders often occurred at highly sensitive times, including during Ramadan, frequently coinciding with iftar or suhoor hours. As a result, the number of unregistered displaced persons—those not recognized by UNRWA—grew significantly. This meant they received none of the limited aid that was distributed to registered refugees, which many have already described as insufficient in meeting basic needs. With the rising cost of living and skyrocketing rents, many families were forced to crowd into relatives’ homes or share a single rented apartment among multiple families, straining already limited resources and space.

With many displaced families settling in surrounding villages—either due to having relatives there or the relatively lower cost of rent compared to the city—returning to the city to manage daily affairs, complete administrative tasks, or attempt to retrieve belongings from their homes in the camps has become both exhausting and costly.

The Israeli army’s frequent road closures, military checkpoints, and harassment of travellers have further obstructed movement, turning even the most basic tasks into logistical and psychological burdens.

Roughly three months after the invasion, the initial surge of charitable aid—largely spontaneous and community-driven—has significantly dwindled. Although UNRWA distributed food parcels and provided limited financial assistance in the form of rent stipends, and despite the Tulkarem governorate’s formation of the “Dignity Committee” (which brought together a broad coalition of governmental and civil society institutions and pledged to cover the rent for hundreds of apartments along with material and financial aid), these efforts have proven insufficient in meeting the needs of the large and growing displaced population.

Many landlords are now demanding rent payments in six-month or annual lump sums, placing further financial pressure on families already struggling. Meanwhile, owners of temporary shelters—such as cultural centers and event halls—have recently begun asking displaced families to vacate, as they seek to resume normal operations and reclaim their only source of income. This has made it even harder for displaced families to find stable alternative housing.

The displacement of refugees and resulting overcrowding have triggered a host of social consequences, most visibly reflected in rising tensions and disputes within host communities. The strain has also taken a serious toll on physical and mental health, with increased exposure to viruses, psychological trauma, and chronic stress becoming widespread.

One of the most acute impacts has been on children’s education. Following the invasion, many children were forced to drop out of school for varying periods. Since the beginning of the second academic semester—shortly after the incursion—both government schools and UNRWA schools (72 public schools and 10 UNRWA-run schools) were forced to shut down and switch to online learning.

However, many displaced or stranded camp students lacked access to even the most basic resources—such as internet, devices, or safe learning environments—effectively cutting them off from education and deepening the long-term consequences of displacement. With families unable to provide their children with the necessary devices for online learning, and frequent electricity and internet outages. This severely disrupted the education of thousands of students enrolled in UNRWA schools.

While most public schools in the two governorates resumed in-person classes after April 7, 2025—following Eid al-Fitr, nearly two months after the invasion—UNRWA schools gradually followed, operating part-time in afternoon shifts within government school buildings. However, the widespread displacement and dispersal of students since the start of the invasion prevented many from returning to their original schools.

A significant number of displaced students had already enrolled in public schools in their new locations of refuge, further complicating efforts to restore continuity in their education and leaving many caught in a limbo between disrupted schooling and unstable living conditions.

Erasing the Traces of the Nakba: Redesigning Camps to Erase Historical Roots and Identity

In its latest invasion, Israel employed a new level of systematic destruction guided by pre-determined plans aimed at redrawing the physical structure of the refugee camps. The operation included carving out new roads and forcibly reshaping the camps into what the military describes as “neighbourhoods”—an effort to strip them of their distinct character and identity through erasure of history and memory.

The tightly packed, labyrinthine layout of the camps—often compared to interlocking Lego pieces—has long hindered the army’s freedom of movement and obstructed surveillance and control. By forcibly redesigning these spaces, Israel seeks to erase their historical and symbolic identity. These camps are, by nature, rooted in the Palestinian right of return and stand as living markers of the refugee issue. The reconfiguration aims not only to sever them from that political and historical context, but also to undermine UNRWA’s presence and role within them.

Demolition at Full Force: Systematic Erasure of Camp Housing

The destruction of refugee camp homes remains at its peak. In Jenin Camp alone, the Israeli military has completely demolished 600 homes and rendered another 3,000 housing units uninhabitable. In the Nour Shams and Tulkarem camps, more than 400 homes have been entirely levelled, with over 2,500 others partially damaged. Additionally, the Israeli army has issued military orders to demolish 58 housing units in Tulkarem Camp and 48 in Nour Shams—targeting entire multi-story buildings that housed hundreds of families.

The evacuation process is deliberately exhausting. Families are often forced to reach their homes on foot under extreme pressure. Recent evacuation operations have grown increasingly aggressive, involving both pre-announced and unannounced demolitions. Some families were given as little as three hours to vacate, with no access to transport—prohibited even from using Red Crescent ambulances. Israeli forces repeatedly attacked medical teams and barred them from timely entry, leading to homes being razed with all furniture and belongings inside.

As demolition orders continue to be issued, many camp residents—some without official warnings—have rushed back to salvage what they can or to check on homes they’ve been barred from for months, fearing unannounced destruction. These return attempts have been met with violent expulsions. To this day, the wave of demolition remains ongoing.

Mass Demolition Orders and Collective Shock

On the night of May 1, 2025, Israel issued a sweeping demolition order, attached to vague aerial maps that ambiguously marked threatened buildings without specifying details. At dawn, residents surged into the Jenin and Tulkarem camps—staggered by the scale of destruction and confused by the lack of clarity about which buildings were slated for demolition. Journalists followed closely behind to document the scene.

It didn’t take long before Israeli forces descended to violently disperse the crowds. Using tear gas, rubber bullets, and live fire, they assaulted and expelled residents from the area. Hundreds of men and women were detained, searched, and held for hours before being released—among them a photojournalist. One female journalist was injured by shrapnel to her leg.

In the following days, access to the camps was severely restricted. Only small groups of residents were permitted entry after thorough searches, while all media were barred, effectively sealing off the demolition zone from public scrutiny.

Adapting to Displacement: Fears of the Temporary becoming Permanent

The occupation leaders continue to confirm their intention to resume their invasion of the camps for months, up to the end of this year, as stated by the Minister of the Occupation Army Yisrael Katz, and recently confirmed by the commander of the Ephraim Region Brigade, Netanel Shamka, who said that their presence “will not last forever, but for now they cannot leave,” referring to “the importance of keeping the forces on the ground,” and explaining “we maintain continuity of work. If we don’t mow the grass, they will recover.” With these statements, the fears of the IDPs are growing, calling for a quick return to their homes in the camp or to their rubble.

In parallel to these statements, the governorates of Jenin and Tulkarem announced, after a meeting with the Prime Minister on 19th May 2025, that they had agreed on a solution to “expand the area of temporary shelter” by providing “caravans” for displaced families who need shelter on different lands.” Tulkarem governorate announced “organizing rental contracts for displaced people from Tulkarem and Nour Shams camps” especially for those who have not found shelter, as both measures are being implemented together according to the governorate’s public relations department.

These solutions, as much as they try to find an approach to contain the real suffering of the homeless, raise the fears of the displaced, who have become aware of the occupation’s plans to turn the camps into ‘neighbourhoods of the city, without more than half of its population being able to return to it after the destruction’, which they see as a blurring of the refugee issue by erasing the camps. Therefore, protesting voices from the residents of the two Tulkarem camps were raised in front of the governorate headquarters in Tulkarem, demanding that the Palestinian Authority work to return them to their homes in the camps, instead of finding alternatives to them, fearing that the temporary will become permanent, erasing the impact of the first crime of displacement.

Weeks after the invasion, Palestinians began attempts to restore a minimum level of daily life, forced to adapt to the presence of the occupation to secure their needs and their depleting income. Given that the occupation expressed its explicit desire to return life to the cities, during a meeting between the Israeli Civil Administration officer and the mayor of Jenin and the director of its Chamber of Commerce, encouraging the opening of shops and repairing streets and proposing to cover the costs – while excluding the camps from this – its goal has become clear to facilitate their daily lives and normalise its close presence among them, with the possibility of storming their streets, shops and homes and arresting them at any moment, while the scene of the destruction of the camps remains a reminder of the fate of those who try to stand up to it.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the above provide scenarios of the potential outcomes that the occupation may aspire to achieve, given the absence of any obstacle to prevent them, the bleakest and darkest of which is its permanent stay in the camps, according to Katz’s statement about “studying the establishment of permanent military posts in the heart of the northern West Bank camps,” while some have extended their concerns to a more distant point you may hear in the conversation of a refugee, such as: ‘this occupation could transform into settler colonialism.’

It is increasingly evident that the objective behind this sustained military presence goes beyond eliminating armed resistance. The strategy appears to center on terrorizing Palestinians to the point where not only are armed actors driven out, but the broader population becomes conditioned to reject any form of armed resistance within their space.

The systematic brutality—widespread repression in both camps and cities—and the forced reengineering of refugee camps to institutionally and symbolically sever them from the refugee cause, UNRWA, and the right of return, together point to a deeper strategy: to reshape the very foundations of Palestinian consciousness and motivation.

This strategy seeks to replace collective resistance with an instinct for individual survival—deepened by existential threats to their homes, safety, and future. As Palestinians watch the ongoing annihilation in Gaza unfold without deterrence or accountability, a pervasive sense of insecurity and impermanence is being etched into their reality.

This policy is far from new. The Israeli occupation has long employed collective punishment and extreme violence in response to even the faintest signs of resistance. It is a strategy rooted in a deeply entrenched security doctrine aimed at extinguishing Palestinian hope in resistance itself—transforming it into an option so costly and traumatic that Palestinians ultimately reject it by their own volition. This is the essence of what has come to be known as the “cauterization of consciousness”: a psychological operation induced by overwhelming violence and unbearable consequences.

Today, this policy is manifesting in its most violent and aggressive form yet. It reflects the mindset driving Israel’s current leadership—dominated by a messianic far-right that is intent on “resolving” the conflict through force. Israeli Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich’s so-called “Decisive Plan” epitomizes this approach. Contrary to the conventional Israeli narrative that Palestinian resistance stems from despair, Smotrich asserts that it arises from hope. Thus, the core of his strategy is to kill that hope—obliterating not just resistance, but the very belief that freedom, return, or justice are possible.

In light of this grim reality, it is imperative for Palestinians to ask hard questions—questions that probe not only the occupation’s strategies but also the adequacy and direction of current Palestinian policies and choices, both official and grassroots.

There is a pressing need to reassess the entire national approach, grounding it in a deep, honest understanding of the lived reality of people on the ground—those who ultimately bear the heaviest costs of any decision. This understanding must serve as the foundation for a renewed national strategy—one that prioritizes the preservation of Palestinian presence on the land and safeguards the collective hope that is increasingly under assault.

In this phase of the struggle, hope itself has become a battleground. Preserving it is not merely an emotional imperative, but a political and strategic necessity—one that can anchor a resistance rooted in dignity, endurance, and a reimagined sense of purpose.

[1] Source: Abeer Ismail, Acting Director of the UNRWA Media Office, after I contacted her.

[2] Returning to the list of martyrs, limiting the search and filtering the results to show the number of martyrs between January 2023 and May 2025, specifically in the cities of Jenin and Tulkarm, shows that the number of martyrs in the two cities is 580, the vast majority of whom were martyred inside the two cities and their camps.

The popular committees in Jenin, Tulkarem and Nourshams camps, the Tulkarem governorate and a local official from Jenin stated that the camps and the two cities have become disaster areas, uninhabitable several times over the past year. I met Faisal Salameh and Nihad Shawish, the heads of the two popular committees, in person last year and they confirmed that the camps are doomed and unfit for human habitation: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.

[3] Source: https://www.palestine-studies.org/ar/node/1657261

NOTE: This text is adapted from original Arabic article.